Visualizing the geometry of familiar three-dimensional space, though admittedly with some additional assumptions that will seem contrived, it is possible to understand an important aspect of the way that a black hole isolates its interior from the rest of the universe.

Let’s start by looking at three-dimensional space in a specific way. In the middle of this space, we draw an axis – in the following image the vertical blue line:

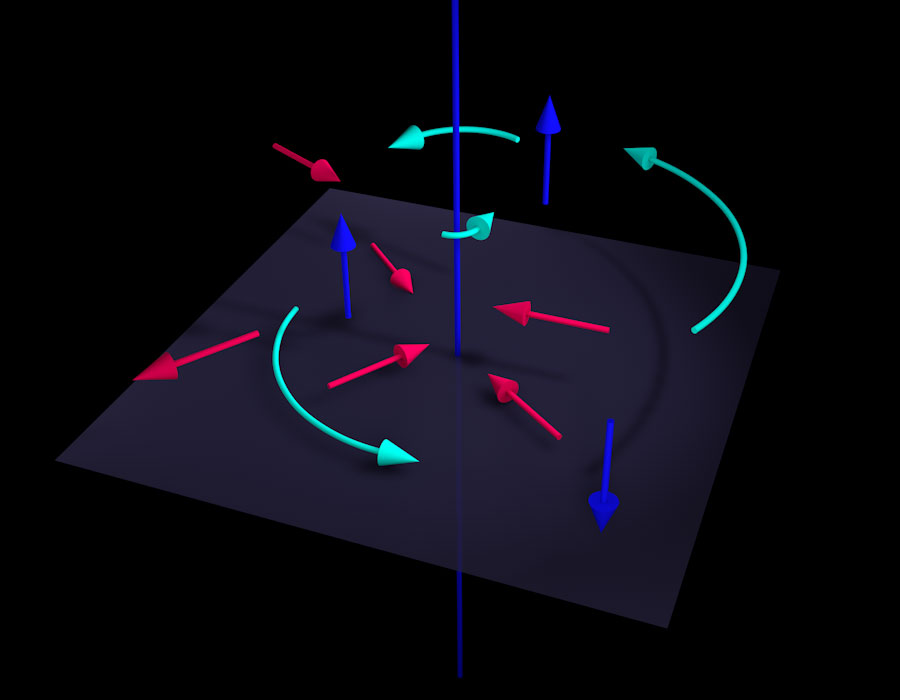

Let’s look at objects moving around in this space. We can define three distinct types of motion. The first has objects moving parallel to the blue axis – either directly upwards or downwards -, so let’s call this axis motion . The second is radial motion – either directly towards the blue axis, or directly away from it. The third is motion perpendicular to the other two, which we shall call angular motion. An object in pure angular motion will trace out a circle around the central blue axis.

If an object is moving in a general way, we can identify the different kinds of motion involved: By measuring how far that object progresses in parallel to the axis, we determine its axis motion; by measuring how its distance from the axis changes, its radial motion; by tracking its motion sideways around the axis, its angular motion. Conversely, if we know all three components of the object’s motion, we can reconstruct the motion as a whole.

We can represent the three kinds of motion by arrows tracing the path of an object following only that kind of motion – moving only radially, or only along the axis, or in pure angular motion. The next illustration shows a few examples – movement parallel to the axis in blue, movement in the radial direction in red, and movement in the angular direction in cyan. This time, we look from a somewhat higher vantage point down onto the gray plane:

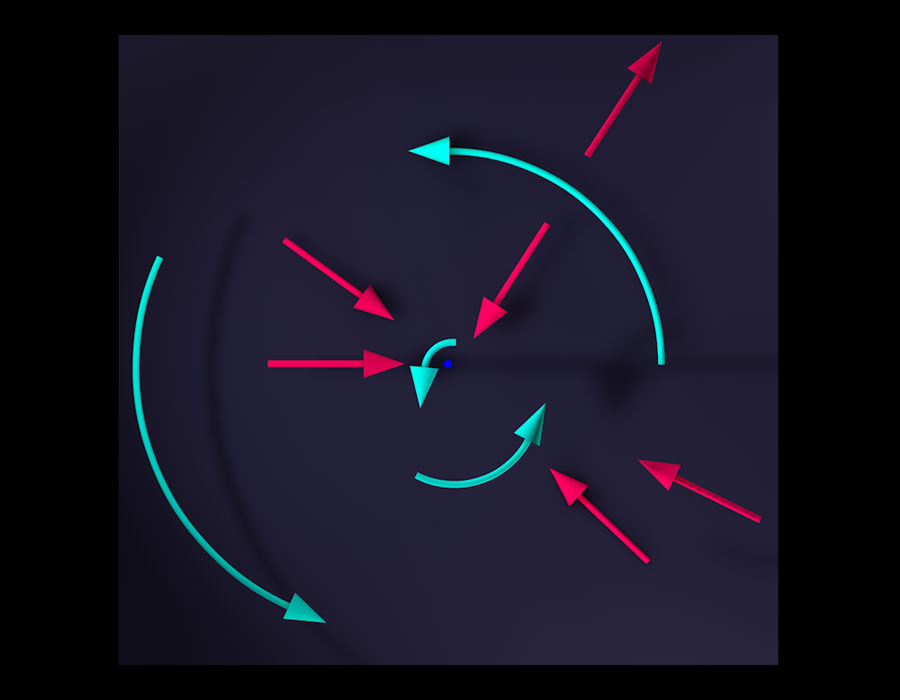

If you’re still somewhat unsure what radial and angular motion are all about, the picture below will hopefully make matters clear. It shows the view of an observer looking straight down at the gray plane. Now the blue axis is no more than a blue dot. We’ll leave out all motion parallel to the axis and only look at the same assortment of radial and angular arrows as in the previous picture:

From this perspective, it is perfectly obvious that the arrows representing radial motion (red) always points straight at or directly away from the axis, while motion in the angular direction (cyan) traces out part of some circle around the axis.

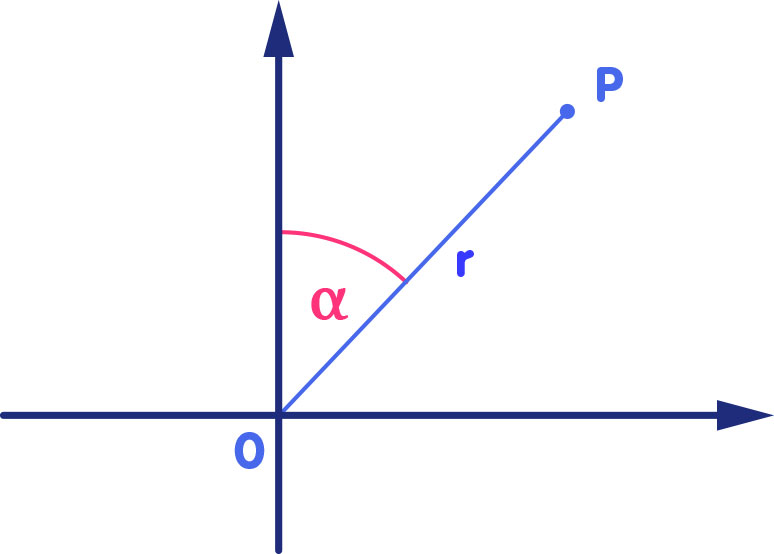

In fact, with this view, it is only a small step to see why we have called those directions radial and angular in the first place. In a polar coordinate system such as is shown in the following image, the location of every point P is defined by drawing the connecting line to the origin and then noting the length r of that line and the angle α between the connecting line and some pre-defined axis:

All points with the same value for r lie on a circle with radius r – hence r is called the radial coordinate. Radial motion is motion that changes only the radial coordinate of an object, angular motion changes only its angle α.

So far, we have done nothing but to introduce a specific way of viewing motion in ordinary, three-dimensional space. (A mathematician would say that we have introduced “cylindrical coordinates” to describe such motions.) Now, let us introduce a restriction – a traffic rule for moving objects, if you will. The rule is this: Upwards axial motion is compulsory.

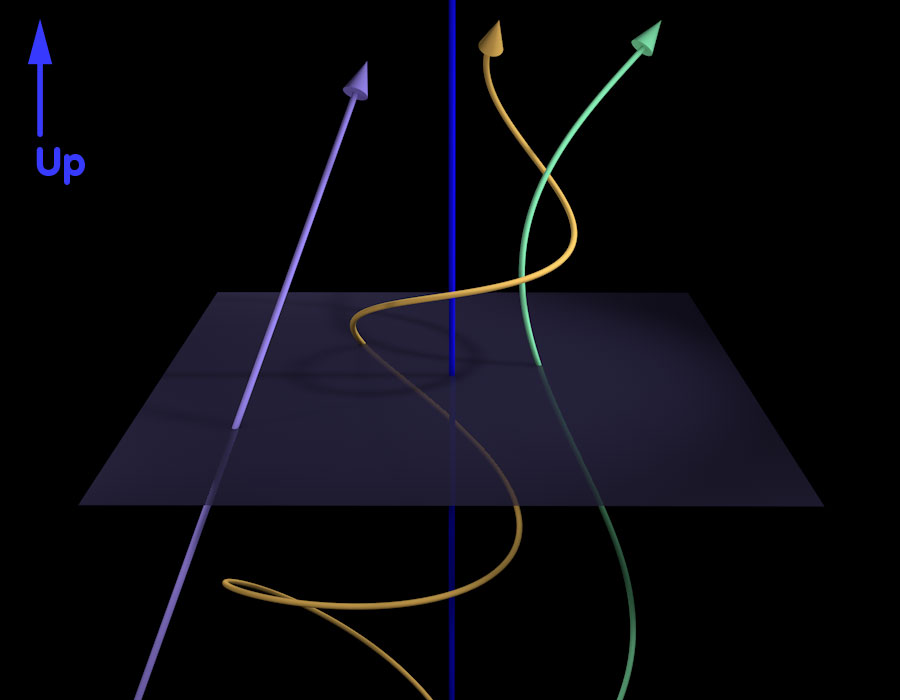

Following this rule, objects still have great freedom. They can move towards the axis or away from it, or simply stay at a constant distance. As far as angular motion is concerned, we do not care whether they move around the axis clockwise, or counterclockwise, or not at all. The only thing we demand is that their motion include a noticeable component that makes them drift further and further upwards. Here are a few examples of the resulting paths:

Whether the path is straight (cyan line), wavy (yellow line) or winds its way upwards in the shape of a helix (magenta line) – we don’t care, as long as the motion always has an upward component.

Why this arbitrary rule? The answer is that, as mentioned in the introduction, the three-dimensional space we have been looking at is meant to be part of an analogy. The real world analogue of the axial direction is meant to be time, and axis motion is meant to be the “motion of objects in time” or, in other words, the fact that, for objects, time passes. Radial and angular motions correspond to motions in space (or, more precisely, motions on a two-dimensional surface that we will take to represent space).

What does this mean? If you trace an object’s path from the bottom upward, you are tracing its progress in time. If the radial and angular position of the object changes as you go upward, that means the object is moving. In this context, the seemingly arbitrary requirement that all paths should drift steadily upward is quite plausible: Time passes for all objects – there is now way to remain at one particular moment (and thus to avoid the future) or, worse, to go backwards in time!

With this identification of the upward direction with time, the images above are what physicists call spacetime diagrams.

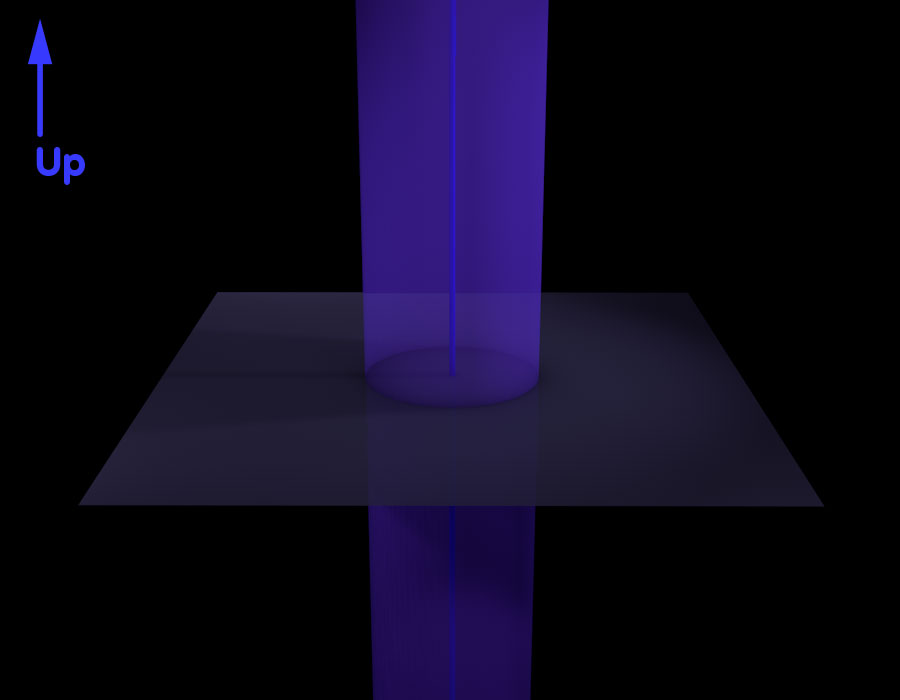

But let’s forget this analogy for a moment, and go back to our space with axial, radial and angular motions. In this space, we introduce an additional feature: A cylindrical surface at constant distance from our blue axis. It is shown in the following illustration in pale blue:

Also, we modify our set of rules. Outside the cylindrical surface, all is as it used to be: Objects can move as they like, as long as their motion includes a definite upwards component. Inside the surface, though, there is a twist: Inside the cylinder, radial and axial direction switch places . Outside the cylinder, motion in the radial direction is not constrained at all. Inside the cylinder, motion in the axial direction is not constrained at all. Outside the cylinder, the axial direction defines a one-way-street: All motion must include an upward component. Inside the cylinder, a similar restriction applies to radial motion: Every object’s motion must include a noticeable inward component .

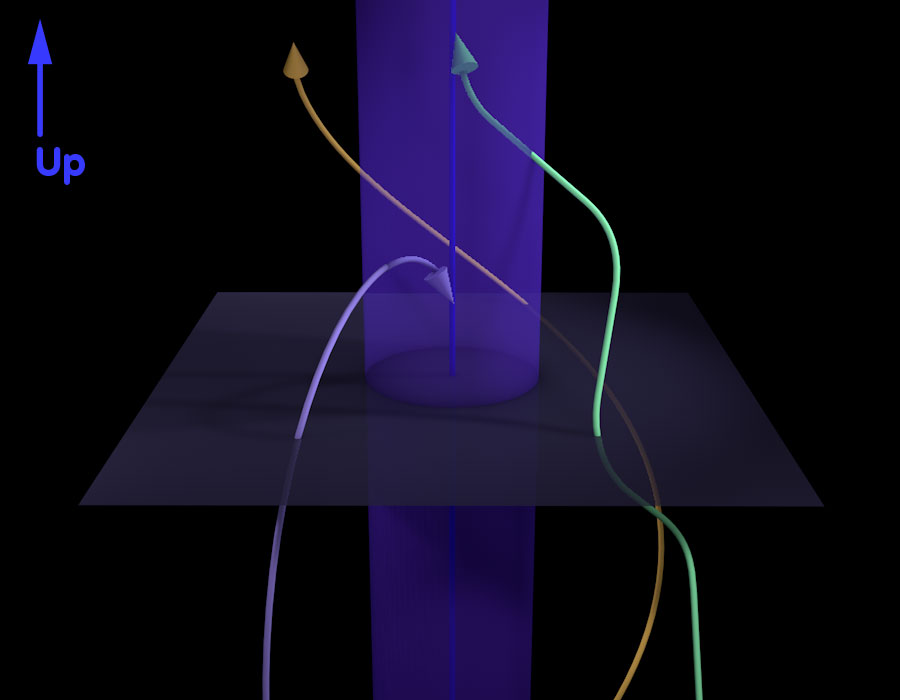

What are the consequences of the new rules? Outside the cylinder, nothing changes – we have the same allowed paths as before. Once an object enters the cylinder, though, it is doomed – from then on, its motion must contain an inward component. In particular, this means that no object that has entered the cylinder can ever leave. The compulsory inward component will lead the object ever closer to the central axis. Here are some examples of allowed motion in and around the cylinder:

You can see that while it is still outside the cylinder, the magenta path leads a particle away from the axis, then a bit closer, then away again. But as the path intersects the surface, this freedom of choice is curtailed – the rest of the path leads the particle strictly inwards.

For the cyan path, you can see that, outside the cylinder, it leads steadily upwards, in accordance with our main traffic rule. However, once inside the surface, axial motion is no longer constrained. As you can see, once this particular particle is inside the surface, it moves a bit downwards again.

Finally, for paths that remain outside the cylinder, such as the yellow path, nothing has changed. All particles remaining outside must have some upwards part to their motion at all times.

Note, though, that there is one problem with our new rule. As soon as an object reaches the axis, we (and it) are stumped. On the axis, no further inward motion is possible, so what is an object to do? There is no way for it to continue its path – no way to obey the rule and continue inwards. We must take such an object out of the game altogether, which is the only way to avoid an infraction of our traffic rule. This isn’t very satisfactory. Evidently, the axis is a location were things go wrong.

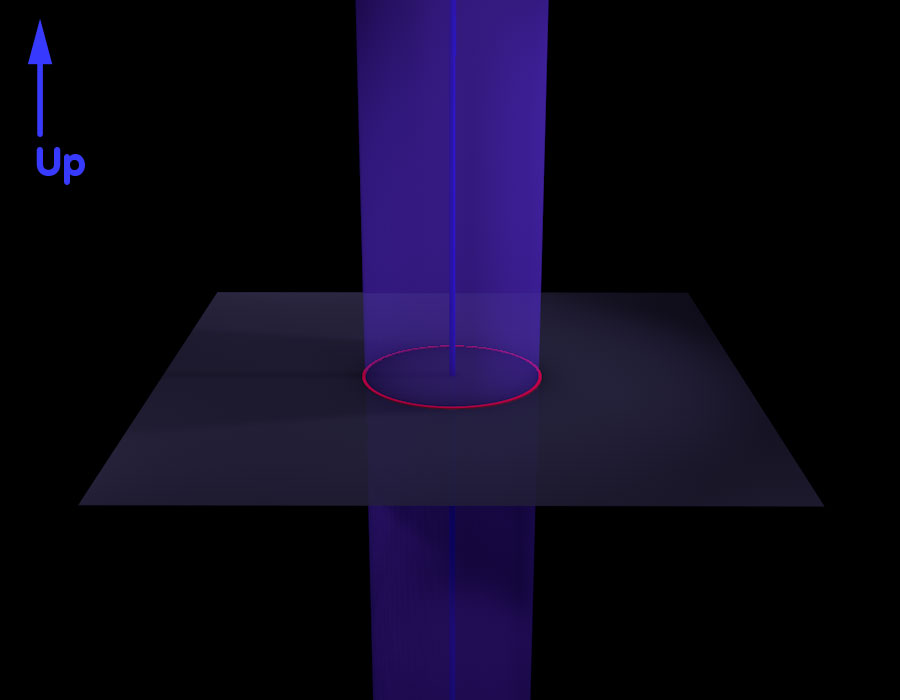

So much for space. But how do the new rules apply to our analogous space-time-picture? We use the same guiding principle as before: The direction to which the one-way rule applies will correspond to time , all other directions will be directions of space. Thus, outside the cylinder, the axis direction must again be identified with time. From the outside, the cylinder looks like the boundary of some region of space: At each moment in time (at each constant height along the axis), space, represented by a plane at right angles to the axis, has an inside boundary defined by the cylinder. In the following illustration, one such plane is shown (the one that has always been included in our images before), and the inner boundary is indicated in red:

But inside the cylinder, matters are radically different. The time direction – the one-way direction – now corresponds to the radial direction, while the axis direction is just another unrestricted space direction. In a way, space and time have changed places!

This has remarkable consequences for the way that objects move as time passes. Outside the cylinder, everything is as it was before. But once an object crosses over into the cylinder, it is trapped. Remaining at a constant radial value or leaving the cylinder is as impossible for an object as stopping time or travelling into its own past. Once an object has crossed into the region of space bounded by the cylinder, it can never leave. The cylinder is the boundary (the horizon) of a black hole!

As inexorably as time passes, any object must progress towards the central axis. However, as the axis is reached, matters go wrong. Once the object has reached the axis, it can go no further, but neither can it remain where it is. Any continuation will lead it outward, and outward motion – motion backwards in time – is strictly forbidden. Neither is remaining on the axis an option – inwards motion is compulsory! The axis is the analogue of the black hole’s singularity, where our description of space and time breaks down, both in this simple model and in the more complete description within Einstein’s general theory of relativity. As they reach the singularity, objects somehow leave the stage (for more information about singularities, see the spotlight text Spacetime singularities).

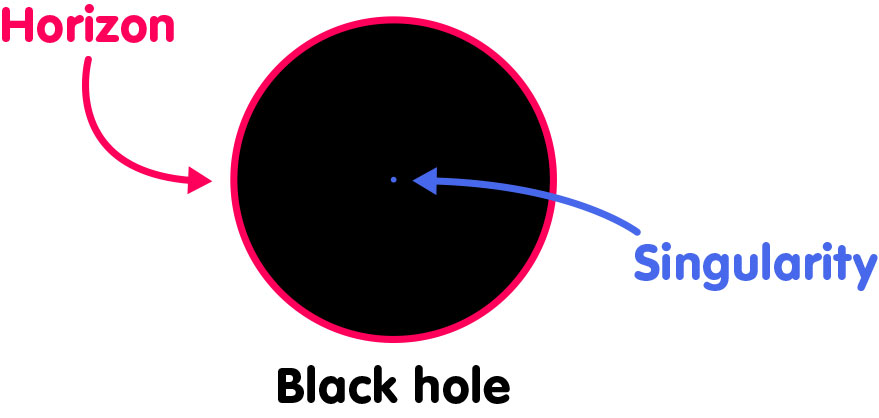

Our analogy is useful in understanding one feature of a black hole singularity that is easy to get wrong. If you hear about a spherically symmetric black hole, bounded by its horizon and containing a central singularity, you are likely to picture a cross-section of the black hole which looks like this:

Here, the circle is meant to represent the horizon, and in the center of the black hole, there is a point – the singularity.

In our three-dimensional model, this picture can be obtained by looking at a plane that is orthogonal to the axis: The intersection of the plane with the horizon-cylinder is a circle, the intersection with the singularity-axis is a point. So is this a snapshot of a black hole, showing its interior structure?

Not quite. Only outside the cylinder does the intersection with a plane at constant height (“at constant time” as seen from the outside) correspond to a snapshot. Inside the cylinder, time and space have switched places. Inside, the intersection image doesn’t show a snapshot – it shows something much more weird: a caleidoscopic combination of many different times. After all, inside, time is not the axial, but the radial coordinate, and all the different distances from the “center” which you see in the sketch correspond to different moments in time. Instead of the spatial structure of the black hole, the sketch shows a strange mix of space and time!

Likewise, if you think about the unstoppable collapse of a body to form a black hole, you might think that the body ends up with all its matter concentrated in a single point of space – the singularity. But again, this picture of the spacepoint-singularity residing in the center of the black hole is simply wrong. Using our analogy, you can see why. The singularity is the whole of the axis – and the axis represents a space direction. Hence, the singularity is not a point in space – it is infinitely extended!

This is exceedingly weird. From the outside, the region of a black hole looks like the surface of a sphere (in our model with two space dimensions and one time dimension, like the circumference of a circle). But inside that sphere, which has only a finite surface area, you can “hide” objects that are infinitely large – infinitely extended in space. How does this work? Again, it works because time and space trade places. Our simple scenario corresponds to an eternal black hole – a black hole that has always existed and will continue to exist indefinitely in the future. From the outside, the black hole is infinitely extended in time, but has only a finite size in space. Inside, the tables are turned: Time is only of finite extent (it starts at the horizon and ends abruptly at the singularity-axis), but instead one space direction, the axis direction, is now infinitely long.

If you have a hard time getting to grips with this mixture of time and space, rest assured that physicists have a hard time visualizing it, as well. Luckily, physicists have a language in which the properties of simple black holes can be formulated very precisely – the language of mathematics -, and using this formulation as a guide, it is possible to develop a pretty good intuition about spacetime containing a black hole.

Our analogy isn’t perfect. In the analogy, the change-over of space and time happens suddenly, at the boundary. In a more precise formulation, the change-over is more gradual. In a way, the time direction is bent more and more inward as you get closer to the black hole. As the bending is strong enough to prevent any object from moving in any direction but inwards, you cross the horizon.

Also, the black hole pictured above is an especially simple specimen. It is spherically symmetric – a so-called Schwarzschild black hole, after Karl Schwarzschild who, in 1915, was the first to write down the equations defining and describing such a black hole; a special solution of Einstein’s equations of general relativity. (However, it took physicists more than fourty years to come to understand the weird spacetime geometry that Schwarzschild’s equations imply!) As has already been mentioned, this type of black hole is eternal – it has always been there, and will always be there. More realistic black holes with a definite beginning (for example those produced by the collapse of a massive star) or eternal black holes which rotate all have a somewhat more complex inside structure.

Apart from these qualifications, the analogy holds, and it does capture an essential aspect of a real black hole’s spacetime geometry – time and space changing places at the horizon, and some fundamental consequences of that exchange.

Relativistic background information for this Spotlight topic can be found in Elementary Einstein, in particular in the chapter Black holes & Co..

More information about singularities and their definition as spacetime boundaries where freely falling objects simply cease to exist, see the spotlight text Spacetime singularities. Other related spotlights on relativity can be found in the category Black holes & Co..

is the managing scientist at Haus der Astronomie, the Center for Astronomy Education and Outreach in Heidelberg, and senior outreach scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy. He initiated Einstein Online.

Cite this article as:

Markus Pössel, “Changing places – space and time inside a black hole” in: Einstein Online Band 04 (2010), 03-1009

What is Einstein Online?

Einstein Online is a web portal with comprehensible information on Einstein's theories of relativity and their most exciting applications from the smallest particles to cosmology.

Einstein Online is provided by the

Includes information on our authors and contributing Institutions, and a brief history of the website.

More than 400 entries from "absolute zero" to "XMM Newton" - whenever you see this type of link on an Einstein Online page, it'll take you to an entry in our relativistic dictionary.

Our recommendations for books and websites on relativity and its history.

© Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, Potsdam ![]()

![]()

time It is a fact of life that not all events in our universe happen concurrently - instead, there is a certain order. Defining a time coordinate or defining time, the way physicists do it, is to define a prescription to associate with each event a number so as to reflect that order - if event B happens after event A, then the number associated with B should be larger than that associated with A. The first step of this definition is to construct a clock: Choose a simple process that repeats regularly. (What is "regular"? Luckily, in our universe, all elementary processes such as a swinging pendulum, the oscillations of atoms or of electronic circuits lead to the same concept of regularity.) As a second step, install a counter: A mechanism that, with every repetition of the chosen process, raises the count by one. With this definition, one can at least assign a time (the numerical value of the counter) to events happening at location of the clock. For events at different locations, an additional definition is necessary: One needs to define simultaneity. After all, the statement that some far-away event A happens at 12 o'clock is the same as saying that event A and "our clock counter shows 12:00:00" are simultaneous. The how and why of defining simultaneity - a centre-piece of Einstein's special theory of relativity - are described in the spotlight topic Defining "now". With all these preparations, physicists can, in principle, assign a time coordinate value ("a time") to any possible events, and describes how fast or how slow processes happen, compared to that time coordinate. surface Geometric space with two dimensions. Examples include the plane or the surface of a sphere. star A cosmic gas ball that is massive enough for pressure and temperatur in its core to reach values where self-sustained nuclear fusion reactions set in. The energy set free in these reactions makes stars into very bright sources of light and other forms of electromagnetic radiation. Once the nuclear fuel is exhausted, the star becomes a white dwarf, a neutron star or a black hole. sphere A spherical surface is a simple example for a curved surface. It is easily pictured as a surface embedded in three-dimensional space: a spherical surface is the set of all points at a certain fixed distance from a given point (the point being the centre of the sphere). Mathematically, a spherical surface can be described without recourse to three-dimensional space - when mathematicians talk of the geometry of such a surface, they (almost) always mean the "inner geometry": Those properties of the surface noticeable to two-dimensional beings, living and working in that surface, capable of measuring distances and angles in it. Sphere is regularly used as a synonym for spherical surface (instead of describing a solid, three-dimensional ball). And not only for the two-dimensional spherical surface described above, but also for its analogues in lower and higher dimensions. A one-sphere, for instance, is the same as a circle, a two-sphere is the spherical surface defined above, a three-sphere its three-dimensional analogue. space In a strict sense: Space as we know it from everyday life: the totality of all locations in which objects can sit, with three dimensions. In a more general sense used by mathematicians, all kinds of sets of points are spaces - a line for instance, which has but a single dimension, or a two-dimensional surface, but also higher-dimensional spaces. Also, in such more general spaces, geometry can be different from the standard Euclidean geometry taught in high schools - such spaces can be curved. spacetime Already in special relativity, observers in motion relative to each other will not, in general, agree as to whether two events happen simultaneously, or as to how great is the distance between two objects. They do, however, agree as to what events there are, although not to when and where they happen. This observer-independent totality of all events is called spacetime. How spacetime is split into space and time can differ from observer to observer. Every-day space has three dimensions. Adding time adds another dimension - spacetime has four dimensions, all in all. We are used to the idea of a point in space - an object that has only one location and is completely defined once its space coordinates are given. In spacetime, a spacetime point is an object defined completely once its space coordinates and its time coordinate are given - which makes a spacetime point nothing but an elementary event. The idea of spacetime is, in addition to its role in special relativity, a building block of general relativity. Analogous to how a plane is flat, but the surface of a sphere is curved, in general relativity, curved or distorted versions of the simple, flat spacetime of special relativity play a role. Spacetime curvature, in general relativity, is intimately connected with gravity. For an introduction to the basics of both theories of relativity, check out the chapters Special relativity and General relativity in Elementary Einstein. Sometimes, it can be helpful to view spacetime in analogy to ordinary space - such analogies are explored in the spotlight topics Time dilation on the road (for time dilation) and Twins on the road (for the twin effect). solution In the context of general relativity: a solution or, more precisely, a solution of the Einstein equations is a model universe that follows the law of gravity as prescribed by general relativity. See also exact solution. singularity Irregular boundary of spacetime in general relativity - region where spacetime simply comes to an end. Often, such boundaries are associated with spacetime curvature growing beyond all bounds and becoming infinitely large - so-called curvature singularities (notably Ricci singularities or Weyl singularities - but there are exceptions (for instance a conic singularities). According to general relativity, a singularity exists inside every black hole, and the starting point of any universe described by a big bang model is a singularity as well. The occurrence of singularities is a failure of general relativity - and a strong indication that the theory is incomplete. Instead, one could describe the earliest universe and the interior of black holes using a theory of quantum gravity. More information about singularities can be found in the spotlight texts Spacetime singularities and Of singularities and breadmaking. Schwarzschild black hole A solution of Einstein's equations found by Karl Schwarzschild in 1916, which corresponds to a model universe that contains a single, spherically symmetric black hole. More precisely, the Schwarzschild solution is a whole family of solutions: Schwarzschild's formulae contain a free parameter m corresponding to the mass of the black hole. To each concrete value of m corresponds one specific solution to Einstein's equations, a spacetime containing a spherically symmetric black hole of mass m. The Schwarzschild solution is of practical importance as the outlying regions of the corresponding model universe describe the spacetime distortion around all kinds of objects that are spherically symmetric, or nearly so, such as the sun or the earth (cf. Birkhoff's theorem). point Elementary "building block" of geometrical entities such as surfaces or more general spaces. For instance, a surface is the set of all its points, of all possible locations on the surface, and all geometrical objects in that surface are defined by the points that belong to them - for instance, a line on the surface is the set of (infinitely many) points. plane A surface within which the axioms of Euclidean geometry (synonym: plane geometry) hold - the rules of geometry as they are taught in high school, with well-known formulae such as Pythagoras's theorem and "the perimeter of a circle is 2 times pi times its radius" hold. observer In the context of relativity, "observer" can mean two different things. Often, observer is synonymous with reference frame or (spacetime-)coordinate system: An observer in this sense is someone who assigns coordinates to everything that happens around him. In particular, all events are assigned space coordinate values and a time coordinate value. In the context of special relativity, it is often the case that when one talks about an observer, what is really meant is an inertial observer, corresponding to a special type of reference frame. On other occasions, the term is used in a more narrow sense - in those cases, an observer is someone sitting at a certain point in space and using the light signals reaching that location to construct an image of his surroundings. In the context of optical effects in relativity, for instance gravitational lensing, observer is usually meant in this way. matter In general relativity: All contents of spacetime that contribute to its curvature: particles, dust, gases, fluids, electromagnetic and other fields. In particle physics: All elementary particles with half-integer spin, such as electrons and quarks, as well as their composites such as protons and neutrons, in contrast with force particles. line Geometric object with a single dimension. A line can either be an independent one-dimensional space (in the abstract mathematical space where a space does not need to have three dimensions), or it can be embedded into a more general space, like a line drawn onto a piece of paper (i.e. a surface). lead Chemical element with the symbol Pb; each lead nucleus contains 82 protons. Lead nuclei, stripped of their electrons, are among the types of heavy ions which are brought into collision in particle accelerators such as the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider in order to recreate the state of matter in the early universe shortly after the big bang. horizon

In general relativity: A closed surface that is the boundary of a black hole. Whatever enters through this boundary from the outside can never again leave the inside.

Synonym: event horizon.